Observation Log

March 25th

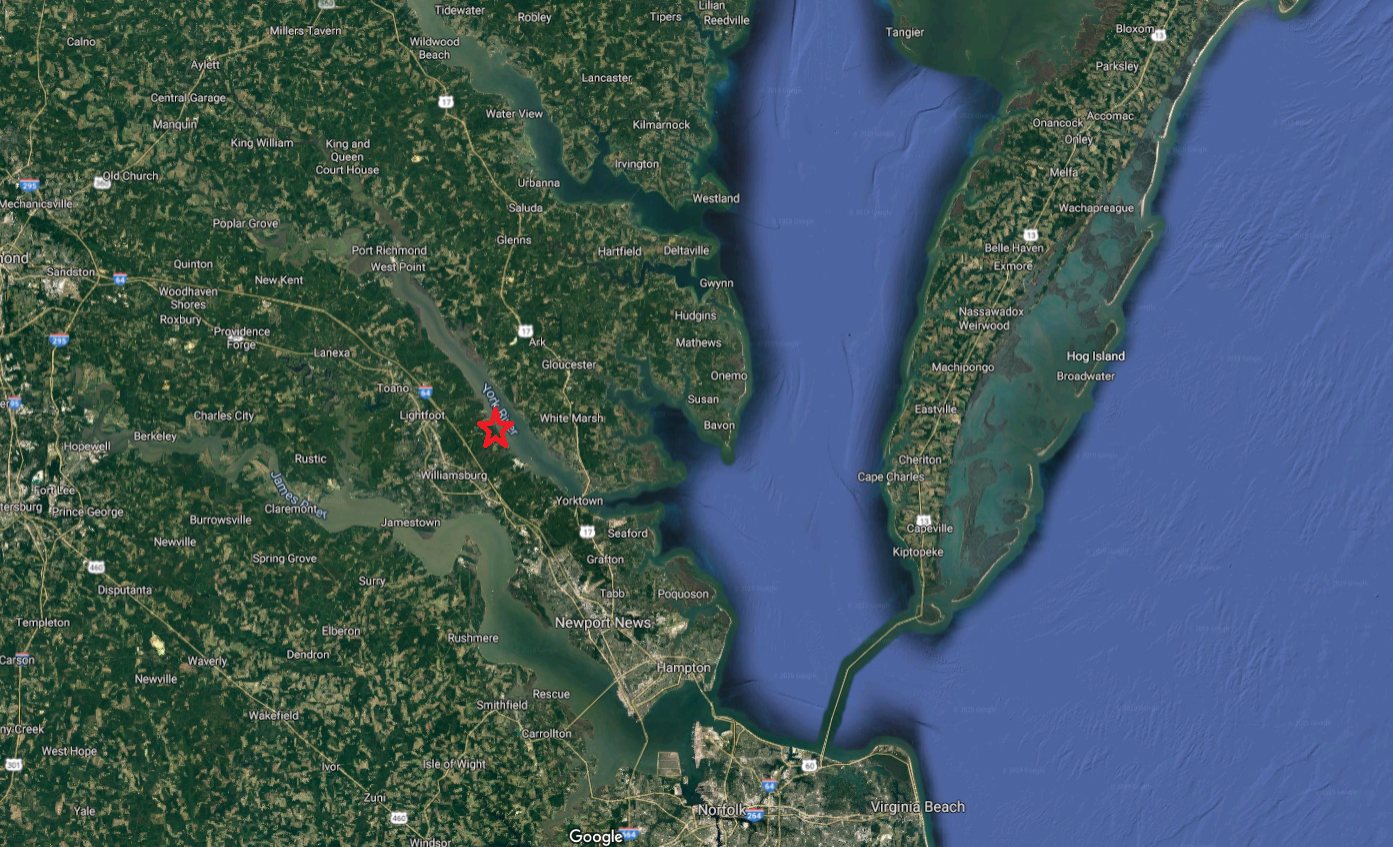

Met with Carol, the Virginia Master Naturalist spearheading the Project Osprey Watch nest monitoring in my area. Today we watched the pair for about 45 minutes. The nest was still fortified from last year and the ospreys were only doing slight patch jobs with sticks, netting, etc. The male was hunting and caught a fish during our time monitoring, however, he ate the fish himself, away from the nest. Carol told me this pair last year raised three healthy chicks, so I am hoping for another successful year. After surveying the marina for a little while with our binoculars we discovered a second nest about 200m away from the main nest we were monitoring. I estimate there are at least 6 breeding pairs on Queens Creek.

March 29th

Not a whole lot of action from the ospreys today. Went down to monitor in the early morning and whatever they say about early birds getting the worm, is not true about ospreys, they were very slow to wake up this morning. The male was perched on a sign near the nest and appeared to be grooming himself. The female was just hanging out in the nest. Quiet morning.

April 6th

This afternoon when I got to the nest I could tell something had changed. The female was sitting very low in the nest and only her head was just popping above. The male was out, probably hunting. Immediately I thought the female had laid eggs and was incubating them. If I am correct, she will be incubating the eggs for the next month or so.

April 12th

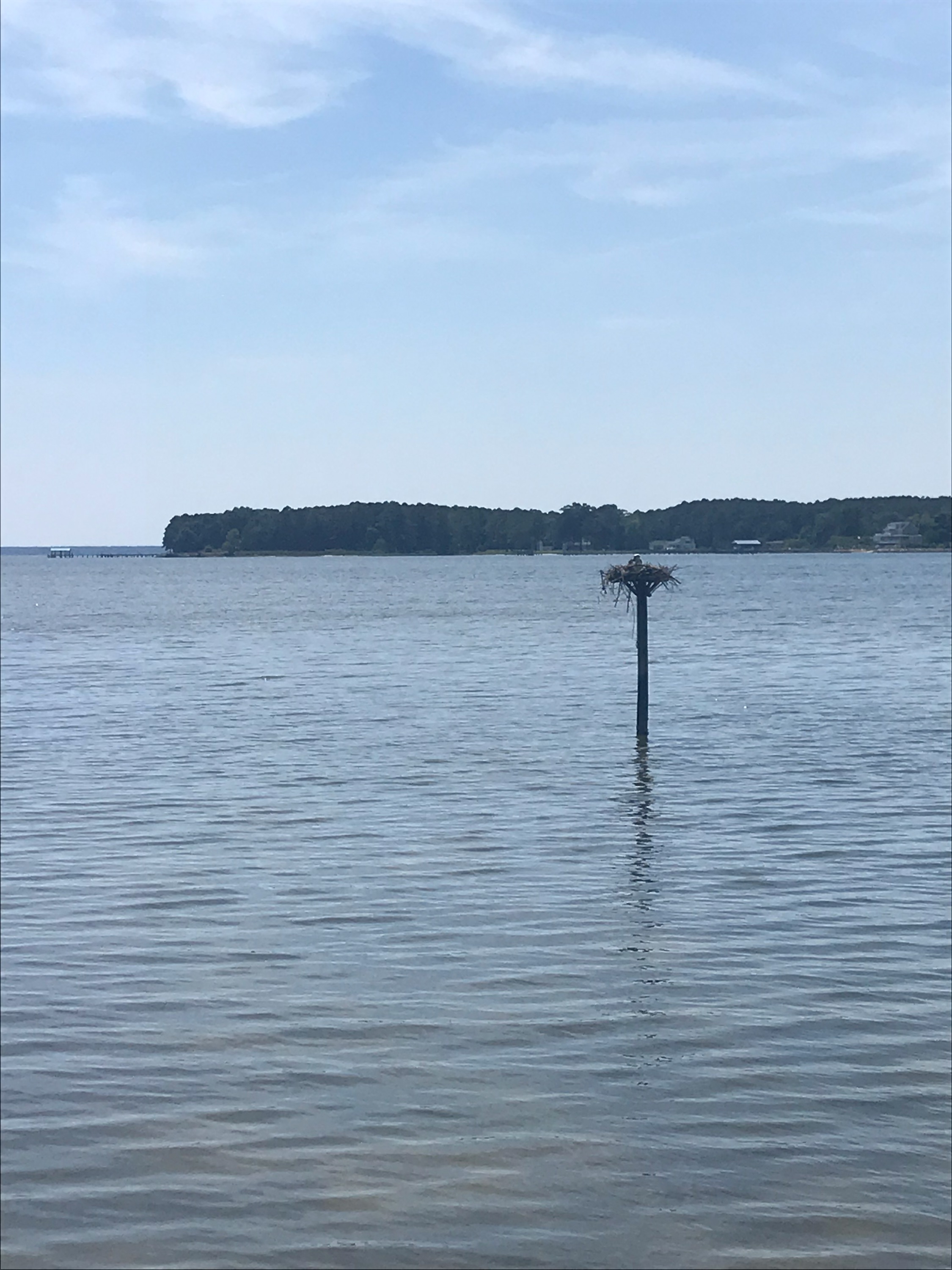

I believe my earlier suspicion was correct, and that the female is incubating her eggs, however, the nest is on an osprey platform on the far side of the channel, so I cannot quite peak into the nest. However, she is still sitting low down, looking around constantly, and not getting up, therefore, I really do believe she has laid her clutch of eggs. The male spends of his time hunting, cleaning himself, and watching the nest from nearby. He doesn’t seem to spend much time sitting at the nest.

April 20th

Based on Carol’s observations last year, the time of year (late spring), and my observations, the female has laid her eggs and they should be ready to hatch within two weeks. Their behavior has remained pretty consistent for the last two weeks. The male spends most of his day hunting for himself and the female and protecting the nest from other osprey. The female is incubating. Hopefully, after a few more visits we will have hatchlings and I will know the brood count.